Remains of the Day: Issue 02

Veblen values, the uncanny valley of interactivity, and Ash is Purest White

I had set aside a day to post a newsletter from Taiwan, where I spent most of the holidays with family, but that day I caught some one-day virus and spent it embracing a toilet in the Airbnb while vomiting repeatedly. Is there any relief sweeter than that from nausea? One minute you’re contemplating the sweet relief of death, the next minute it’s as if the gyroscope in your brain snaps back to equilibrium. The feel of solid earth beneath the feet never felt so good.

Can we all converge or agree upon some standard cables for all our mobile gizmos? I had to bring a whole bag full of USB-C, Lightning, and micro-USB cables of various permutations, along with a few different wall plugs, plus a large USB-C adapter to plug into my iPad and MacBook Pro just so they could accept other cables, and it was not fun. We speak of the dividends of the mobile phone wars, but what about the taxes?

Veblen values

In economics, a Veblen good is one for whom demand increases as the price increases. Luxury goods like Birkin bags are often cited as examples of these exceptional goods that violate the conventional relationship between price and demand.

Social media has created what I think of as Veblen values. That is, values we tend to clutch and defend more vigorously the more expensive they are to hold.

This isn’t odd in itself; we tend to think of values we pay for the most dearly as among the most precious. Freedom. Equality. And so on.

However, social media has opened an exploit on this concept. Others can cause us to rate some values more highly than we might otherwise just by raising the cost to us of holding them.

A troll might mock you as a snowflake on social media for something you posted, and the next thing you know you’re in an online back alley engaged in a knife fight to defend a view which maybe you cared about but not that passionately before the fracas.

Perhaps trolling is just a condition in which there are asymmetric emotional costs to engaging in a debate. Since it’s relatively cheap for a troll to push buttons while the emotional cost to the one whose buttons are pushed is high, the incentive and all the positive optionality is in favor of the attacker.

Sometimes these are values we do hold dearly. The trick, then, is in matching your emotional energy expenditures to the strength of your values prior to factoring in the costs from all the trolls trying to attack you for it. Easier said than done, especially in the West where major social networks have tended to be fairly lax in moderation, and where, not surprisingly, many describe time online as exhausting. Part of this is the performative structure of social media, as I’ve written about before, but some of it is just the emotional attrition of endless border skirmishes.

As with email, I recommend applying aggressive personal spam filters on social media. That saying that one should “feed a cold, starve a fever”? There’s a reason we say “don’t feed the trolls.”

[Speaking of spam filters, I jumped into my Gmail spam folder the other day and realized it had flagged a whole bunch of emails I wanted. When the government comes after Google for antitrust perhaps the overly aggressive Gmail spam filter will be one of the prosecution’s numerous exhibits.]

The Uncanny Valley of Interactivity

I believe mass entertainment suffers from a bit of format rigidity due to the natural inertia from structural ossification in the music, film, and publishing businesses, to name the most prominent.

One of the ways this manifests is in the one-way broadcast nature of much of our entertainment despite the fact that several billion people own internet-connected smartphones now, and even though they consume an increasingly large share of that entertainment on such devices equipped with all sorts of input options and sensors.

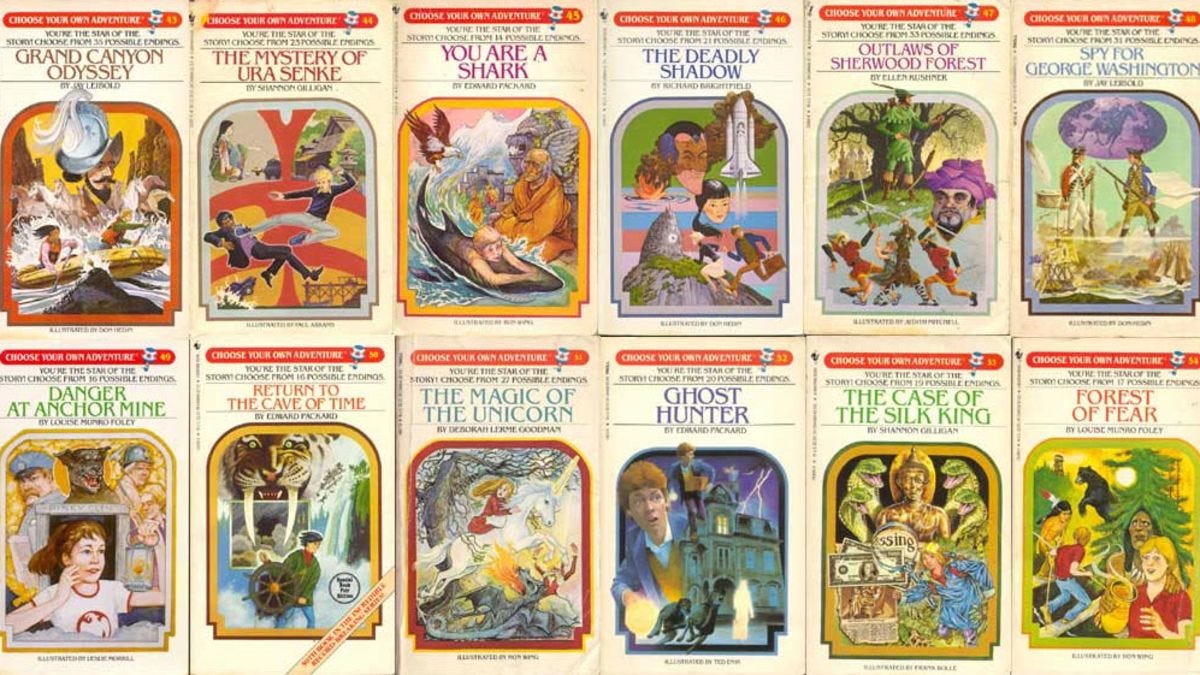

Whenever I say this, however, people seem to want to leap to choose-your-own-adventure storytelling, and the most cited example is Netflix’s Bandersnatch. In its earnings report for 2018, Netflix famously declared “We compete with (and lose to) Fortnite more than HBO.” I happen to agree with them that the threat of gaming looms larger than any other in the future, and it’s not surprising to me that they’ve spun up a group to experiment with interactive stories like Bandersnatch and Bear Grylls’ You vs. Wild.

However, stories like Bandersnatch strike me as falling into an uncanny valley of interactivity. That is, compared to regular movies, they force you to do a bit of annoying work that breaks the suspension of disbelief: the first choice you’re offered in Bandersnatch is which cereal to eat for breakfast. If you’re in the mindset for lean-back entertainment, you can let the story choose an answer for you on its own after some amount of time, but the distracting question prompt is still displayed on the screen.

On the other hand, if you want real interactivity, something like Bandersnatch feels like a low-res step function compared to the continuous interactivity of video games. Why play a busted game with such limited branching when so many great games, many of them multiplayer and synchronous, offer a truly unpredictable and immersive form of interactivity?

However, this doesn’t mean I don’t like contemplating the ripple effects of user choice. One of my favorite story genres, one which I’m not sure has a name, is what I refer to as the recursive escape room genre.

You’re likely familiar with it from its most famous entries. Groundhog Day (in fact TVTropes refers to this genre as the Groundhog Day Loop). Edge of Tomorrow. Russian Doll. A Christmas Carol.

In these stories, the protagonist keeps reliving the same set of events in what feels like an endless loop in time. As they realize their conundrum, they start to experiment and iterate until they eventually come to an epiphany as to why they’re trapped. Then, and only then, can they break out of the loop.

Watching these films reminds me of how I’d read Choose Your Own Adventure books as a child. Every time I came to a choice in the story, I’d dog-ear that page, then eventually revisit it to take the other path, until I’d read every possible branch of the story. However, works like Groundhog Day reduce the effort required of the viewer by simply playing all the branches in a linear fashion, offering both a lean-back viewing experience and the sensation of narrative progression as the protagonist moves closer to breaking out of the loop. Bandersnatch offers the ability to jump back to any decision you made previously and change it through a sort of decision history carousel, but that still requires work on the part of the viewer.

The appeal of recursive escape room movies and TV shows, I theorize, lies in its echo of something many people feel in their lives, that they are trapped in some routine. Wake up, go to work, come home, scrounge up dinner, unwind a bit, then back at it the next day. This genre offers up the possibility that we can puzzle ourselves out of these Moebius prisons which keep depositing us back to the same starting point. Maybe if I stop eating carbs. Or meditate in the morning instead of checking social media. Or start working out before the morning commute. Maybe if I’m more assertive and ask for a raise, or a promotion, which I richly deserve.

I’d guess that the easiest way to predict how any person’s day will go is to look at the previous day. It’s quite plausible that most lived days on Earth feel like a slightly modified replay of the previous day. We all live, for the most part, in recursive escape rooms.

The appeal of self-help gurus and podcasts about the habit of successful people is that they resemble those escape room chaperones who offer occasional hints to groups who get stuck on one particular puzzle. These secrets to success from modern gurus feel like video game walkthroughs except for real life. Sleep more. Eat keto. Lift weights. Delete social media apps. Walk 10,000 steps a day.

That sense of progressive mastery is a hell of a drug. That’s why, while I’m bearish on choose-your-own-adventure films like Bandersnatch, I’m bullish on the right types of light interactivity when it makes sense. If you were designing a game show today, for example, it would likely look much more like HQTrivia than, say, Wheel of Fortune.

Gamification got a bit of a bad rap in recent years, and some of the implementations out of Silicon Valley can feel brutish, to be sure. Still, when I look at the progressive mastery tactics of something like Candy Crush, I can’t help but find them more fun and effective, in some ways, than the Suzuki method of teaching violin playing, or Mr. Miyagi’s “wax on, wax off” school of teaching Daniel Larusso karate.

Movie of the week: Ash is Purest White

Early on in Jia Zhangke’s most recent film, the theme from Once Upon a Time in China plays as the lead character Qiao (played by Zhangke’s wife and muse Zhao Tao) walks through a crowded theater. Later, we hear the Sally Yeh theme song from John Woo’s The Killer. These music choices, like most of Zhangke’s references, strike me as deliberate.

Both tracks position the film in the lineage of heroic Chinese genre cinema. Qiao’s boyfriend Bin is the boss of a small-time crime gang in the city of Datong, so one might guess that Ash is Purest White is just Zhangke taking a crack at a gangster genre film.

The film is about heroism, but of a variety more familiar to Zhangke fans: that of a citizen of one of China’s rural communities trying to cope with the massive economic changes in China. The use of Yeh’s theme song from The Killer reminds us of the gangster codes that used to govern relations among compact tribes of Chinese before political and economic systems stepped in and reconfigured the relationships among the people at a nationwide scope.

Qiao stands defiant against economic and social turmoil and upheaval. Even in the face of Bin’s wavering faithfulness, she is stoic and resolute. In the film, she is the lone testament that the types of brotherhood and loyalty referenced in Hong Kong gangster films like The Killer actually exist.

The Three Gorges Dam project hovers in the background as the economic development project that disrupts the fraternal relations of Datong, transforming most of the gangsters into calculating businessmen. There is always a strain of skepticism in Zhangke’s films about China’s participation in the global economic system, a conservative impulse that flirts with being anti-progress.

Despite that, I was deeply moved by Qiao’s heroic forbearance. Ash is Purest White is a reminder that a single life can be an epic.